The Myth of the Christian Nation

Part I: Freemason Foundations and Dismantling Imperial Mythology

The Lord will be our God, and delight to dwell among us, as His own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways, so that we shall see much more of His wisdom, power, goodness and truth, than formerly we have been acquainted with. We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when He shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations, “may the Lord make it like that of New England.” For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. - John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity,” (1630)

“America is a Christian nation.”

It’s a popular catchphrase I have personally encountered online increasingly, especially among right-wing conservatives. Amidst cultural disintegration, debates over immigration, and escalating distrust in national institutions, Americans are reexamining their national identity to ask a vital question: What does it mean to be an American?

For the political left, this examination has already begun. Following the rise of Black Lives Matter in the early 2010s, academics, corporate journalists, and celebrities alike thrust racial consciousness into the public zeitgeist. This cultural reckoning culminated in The New York Times’s publication of The 1619 Project. For leftists, Nikole Hannah-Jones’ history of the United States was controversial at best and horrific at worst, a shocking revisionist history that seemed to undermine the promises and achievements of the Civil Rights Era. Eschewing the narrative that the United States led the battle for equal rights after the Civil War, Hannah-Jones instead argued that slavery, and thus, racism, was an integral component of American history if not one of its foundational cornerstones. The 1619 Project dared to posit that instead of standing up to imperial injustices and colonialism, the United States had not only led the way in perpetuating systemic oppression, starting with slavery, but continued to practice institutional racism in the 21st century.

Whether this discussion ultimately helped the political left or led to its implosion is a topic for another day, as I believe the political right is now in a similar position. After decades of cultural hegemony, the popular political spectrum has swung from left to right, aiding the political ascendancy of Trump and his MAGA base. However, as is often the case with empires, victories bring questions of identity. If Trump represents America, what is an American? White? Wealthy? Middle-class? Mixed? Working-class? Christian? While the political left seems less concerned with the religious makeup of America, the political right sees religion as an essential component of American identity and has for at least fifty years. Thus, the question of what makes an American necessitates another question. If America is a Christian nation, what kind of Christian is it?

For many American Christians, past and present, the answer has been firmly “Protestant.” Puritans such as John Winthrop certainly hoped that would become the case. In fact, the argument that America is inherently a Protestant nation seems to originate from Puritan culture, which historian Colin Woodard describes as “Yankeedom.” In his tremendous work, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, Woodard convincingly argues that the spirit of “American exceptionalism” originates from the English Puritans and Pilgrims who initially settled in New England. Eager to escape Old England,

The Pilgrims and, to a greater extent, the Puritans came to the New World not to re-create rural English life but rather to build a completely new society: an applied religious utopia, a Protestant theocracy based on the teachings of John Calvin. They would found a new Zion in the New England wilderness, a ‘city on a hill’ to serve as a model for the rest of the world in those troubled times. They believed they would succeed because they were God’s chosen people, bound to Him in an Old Testament-style covenant. If they all did his will, they would be rewarded. If any member did not, they might be punished. In early Massachusetts, there was no such thing as minding one’s own business: the salvation of the entire community depended on everyone doing their part. (55)

We can still see the impact of this belief on broader American Christianity, especially among Protestants. For many, America is uniquely a “city on a hill” because it was inspired directly by God. With the Holy Spirit at the helm, America would lead the way in evangelizing the world. Though Zionists would later integrate the nascent state of Israel into this conception, American exceptionalism long predates the relationship between the United States and Israel. This is no spiritual innovation or mere political tool. Instead, this is a centuries-old and widespread sentiment among American Protestants, including some of the most famous pastors and preachers. Billy Graham asserted that “America has probably been the most successful experiment in history. The American Dream was a glorious attempt. It was built on a religious foundation. Its earliest concepts came from Holy Scripture.”1 His son, Franklin, shared similar remarks on X (formerly Twitter) in 2019.

This conceptualization of America was also prevalent among many of the American Founding Fathers, some of whom argued that America was the land of the free because of its Christian foundation. Famous writer and lexicographer Noah Webster declared in History of the United States that “the religion of which has introduced civil liberty, is the religion of Christ and His apostles… This is genuine Christianity, and to this we owe our free constitutions of government.” (274) In a letter to his friend, Thomas Jefferson, President John Adams argued that “The general Principles, on which the Fathers Atchieved [sic] Independence… [were] the general Principles of Christianity.”2 Despite the incredible doctrinal division among American soldiers (who did not all come from Puritan or even Protestant backgrounds), President Adams maintained that the colonies successfully won their independence from the British Empire because “those general Principles of Christianity, are as eternal and immutable, as the Existence and Attributes of God.”3

Still, whether that Christian heritage was Protestant or not was a matter of debate even among the country’s founders. The Spanish and French colonists who preceded English immigrants imported Roman Catholicism, which remains the largest Christian denomination in the country.4 Additionally, many English immigrants, particularly in the southeastern United States, were Anglican. Although Anglicanism technically qualifies as a Protestant denomination, its liturgical and episcopal character stood in stark contrast to the congregational formats of the Dutch Reformed Church, the Puritans, the Pilgrims, the Quakers, and the Baptists. For many, Anglicanism was equated with English tyranny in general, as the English Civil Wars pitted Anglican Royalists under King Charles I against the Reformed Parliamentarians.5

Then there was the case of those, including several Founding Fathers, whom most American and religious scholars have identified as “deists.” Although all the Founding Fathers were nominally Christian and raised in Christian churches (mostly Anglican and Presbyterian), several espoused values more in line with Enlightenment principles than with Christian doctrine. Despite accusations of atheism during his first presidential campaign, Thomas Jefferson insisted, “I am a real Christian.” Yet “Jefferson rejected what he called ‘the incomprehensible jargon of Trinitarian arithmetic.’”6 As shocking as this may be to orthodox Christians today, Jefferson’s beliefs followed those of his presidential predecessors. Although he was raised as an Anglican, George Washington also seemed more comfortable with unitarian conceptions of God, using “terms such as ‘the Grand Architect,’ the ‘superintending Power,’ the ‘Governor of the Universe,’ [and] the ‘Great Ruler of Events.’”7 His successor, John Adams, “shared in the liberalism that eventually resulted in the separation of Unitarianism from its more orthodox ancestry; he also shared fully in the European Enlightenment, which sought its religious ideas more in Nature and Reason than in biblical revelation or Christian tradition.”8 As we shall see, this may be because Founding Fathers like George Washington were actually practicing occult religion rather than Christianity.

Despite the proclamations of Americans across the centuries that the United States is “one nation under God,” the historical evidence requires us to ask, “Which God?” If even the Founding Fathers rejected the Triune God, this invites us to examine the type of religion that animated America’s founding. I dare to argue that America may be under “God,” but it is certainly not the Triune God. Instead, the history of religion in America reveals a profound and prolific obsession with the occult, which has inspired countless American religious movements from Mormonism and Seventh-Day Adventism to Jonestown and Scientology. American leaders have historically and continue to claim that America is a “Christian” nation, especially a Protestant one, but the reality is quite different. In fact, in practice and belief, America is a pagan nation. Nowhere is this more clear than in the role Freemasonry has played in shaping this country.

Over the next few weeks, I will attempt to demonstrate this argument by presenting the often-overlooked or “forgotten” evidence. This evidence reveals that even before this country’s founding, syncretic pagan religion, especially of the occult type, has been one of, if not the chief, animating spirits of America.

Chapter I: Mythic Origins and Practical Magic

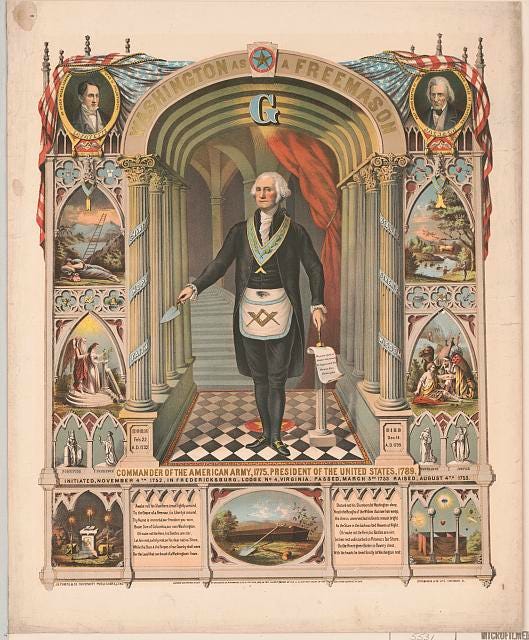

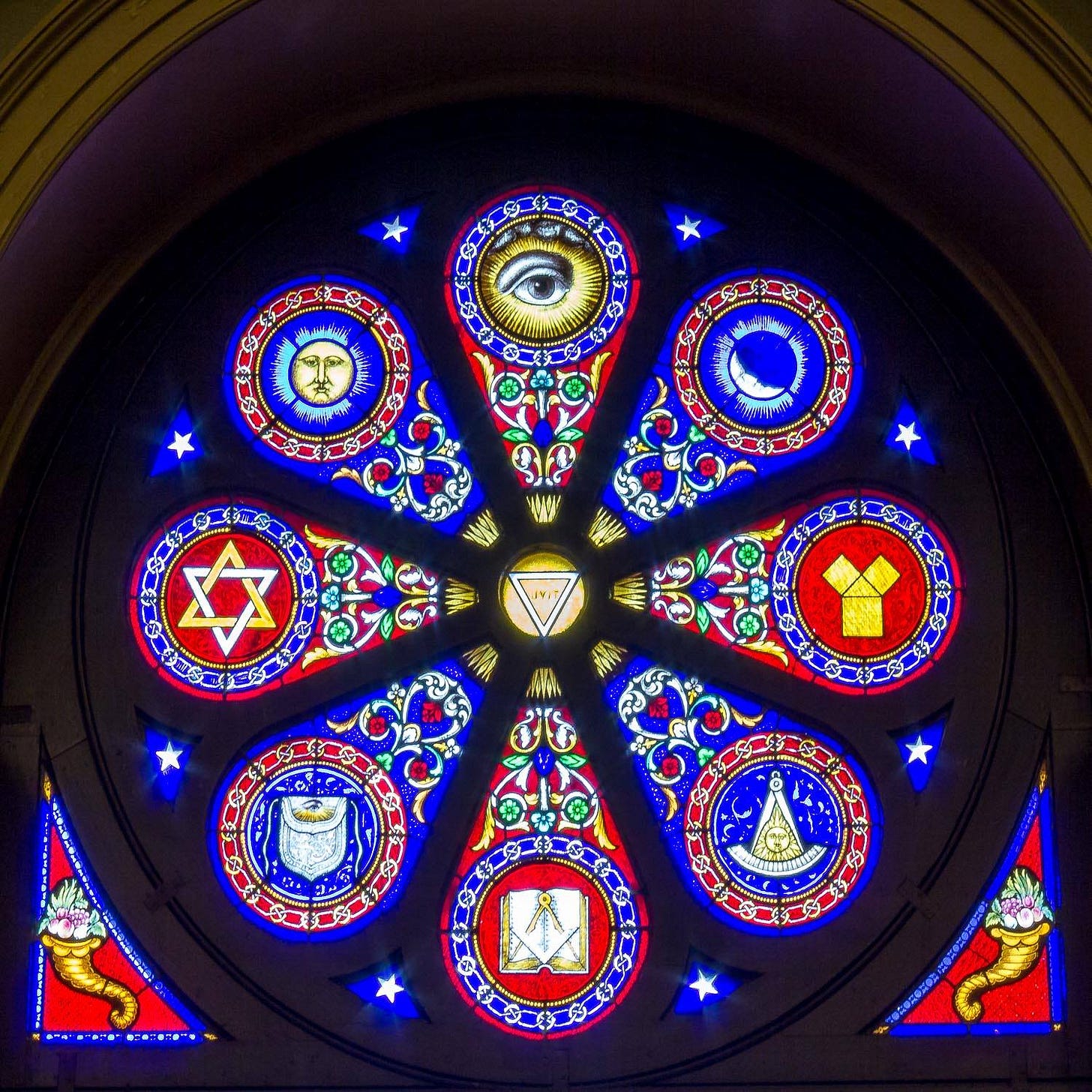

(Pictured above: Inside the Masonic Temple of Philadelphia. Notice the “all-seeing-eye” of the Great Architect and the Seal of Solomon, or Star of David.)

(Pictured above: The back of an American dollar bill. Note the Masonic pyramid and ‘all-seeing-eye’ of the ‘Great Architect'.)

Out of forty-seven presidents, fourteen have been Freemasons. They include George Washington, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, James A. Garfield, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, and Gerald R. Ford. While American historians have often downplayed or blatantly ignored this fact, a significant percentage of our country’s most influential leaders, inventors, businessmen, generals, and celebrities have been members of a secret, occult society. 9

The Rockefeller10 public school narrative of American history traditionally minimizes the role of Freemasonry in the country’s founding, despite the abundant and concrete evidence. Masonic imagery is present across American life, from the Great Seal on the back of the dollar bill to the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, a historical landmark according to the National Park Service. Despite its prolific presence in American society, some insist that Masonry is merely a “fraternity,” perhaps even “the epitome of fraternalism.”11 Other scholars have referred to it as a “civil religion which focuses on freedom, free enterprise, and a limited role for the state.”12 Yet whether we emphasize Masonry’s civic or fraternal nature, we cannot ignore its religious one as well. And as any good classics scholar knows, civic religion is still very much religion.

Although Freemasonry insists that it does not abide by any set of religious dogma, its internal mythology relies heavily on religious precepts. Like many cults, Freemasonry claims archaic origins. For Masonry, these origins predate recorded history. Masons teach that the first human, Adam, had “Masonry written on his heart,”13 which he taught to Cain. Referring to this tradition of secret wisdom as “the craft,” according to Masonic manuscripts, “the craft of initiated builders existed before the Deluge [the Great Flood], and that its members were employed in the building of the Tower of Babel.”14 Although the craft was intermittently lost throughout Hebrew history, Israelites learned the craft while in Egypt, eventually becoming “a whole kingdom of Masons, well instructed, under the conduct of their GRAND MASTER MOSES, who often marshall’d them into a regular and general Lodge while in the wilderness.”15 Eventually, after asking God for wisdom, King Solomon himself learned and utilized the craft to construct his majestic and magical temple.

To this day, Solomon’s Temple remains central to Masonic lore and ritual. Masonic initiation renacts the murder of Hiram Abiff, whom Masons consider to be the famed Chief Architect of Solomon’s Temple. Masonic legend teaches that “when he refused to give up the secrets of a master mason, Hiram was killed with a series of blows to the head.”16 Initiates rehearse this legend by playing the role of the Chief Architect, wherein “he is shouted at, gently roughed up, and then ‘buried’ in a canvas body bag, which is carried in procession around the Lodge. In the end, Hiram Abiff is resurrected by the magic of the Master Mason handshake, and a special life-giving Masonic hug.”17

Here, we can see where Freemasonry has borrowed heavily from Kabbalah, the Jewish occult tradition. In an upcoming essay, we shall explore the impact of Kabbalah on American religion as well.

Yet Masonry does not merely rely on biblical authority. According to Manly P. Hall, one of America’s most knowledgeable experts on esoterica (himself a Mason), King Henry VIII’s personal librarian, John Leland, had discovered that “Masonry had its origins in the East and was the carrier of the arts and sciences of civilizations to the primitive humanity of the western nations.”18 Although such a claim is historically dubious, Masons do contend that the craft is ancient and universal, a “world-wide university”19 of religions and philosophies, ranging from Hermeticism to Christianity. Relying on Masonic sources, Charles W. Heckethorn determined:

But considering that Freemasonry is a tree the roots of which spread through so many soils, it follows that traces thereof must be found in its fruit; that its language and ritual should retain much of the various sects and institutions it has passed through before arriving at their present state, and in Masonry we meet with Indian, Egyptian, Jewish, and Christian ideas, terms, and symbols.20

According to members, Masonry could be found across religions and cultures. This was part of its appeal. Thus, Masonry still maintains that its members (who are exclusively male) can follow any creed, emphasizing brotherly unity over doctrinal division. All its members must believe in a Supreme Being, a divine creator of the universe. Thus, Masonry’s ecumenical inclusivity has made it enormously attractive, especially for post-Reformation Enlightenment intellectuals.

(Pictured above: The Royal Chapel at Stirling Castle.)

Considering the context in which Masonry developed, this makes absolute sense. Although Freemasons claim a mythic past dating back to the Temple of Solomon, the cult’s origins materialized in Scotland during the reign of King James VI (1567-1625). In the early days of the Protestant Reformation, King James was a curious intellectual who filled his court “with everything from poetic theory, medicine and military technology, to alchemy, astrology and magic.”21 In no time, the king’s court became a Mecca for other hungry and bold philosophers. One of those court intellectuals, William Schaw, was responsible for overseeing all royal ceremonies and building projects, including the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle. Schaw purposefully modeled the chapel on biblical descriptions of the Temple of Solomon and received such comparisons with pride. After its successful and lauded completion, Schaw and some of the chapel’s masons began meeting in secret ‘lodges’ to discuss the ancient and hidden wisdoms discovered after the Crusades.

Like many Western Europeans, Schaw and other intellectuals were seeking philosophical answers from the occult after the onset of the Reformation. Although King Henry VIII broke from the Roman papacy in 1534 and formed the Church of England, the question of whether to be Catholic-lite (Anglican) or Protestant would continue to haunt the British Isles. Charles I (1629-1649) reignited the fissure in 1637 when he ordered the Church of Scotland (now united with the Church of England) to adopt the High Anglican form of the Book of Common Prayer. Scotland rebelled, and years of violent conflict ultimately came to a head in the First English Civil War in 1642. Amidst a fracturing society and a divided Church, “all of this made the stonemasons’ version of the Hermetic quest for enlightenment through symbols even more of a spiritual shelter.”22 It is no wonder, then, that the occult became increasingly attractive for war-weary Western Christians.

According to John Dickie, the first reference to Freemasonry can be found during this era in the diaries of Elias Ashmole, an officer in Charles I’s Royalist Army. He recalled his Masonic initiation during his recuperation in Warrington, Lancashire, which the Scottish army had occupied during the First Civil War. It was here, among traumatized soldiers and officers, that the Scottish ‘Lodges’ spread the secret wisdom of the Freemasons; a trend that would also occur in the American colonies. Like Schaw, Ashmole was an ardent alchemist, and “his insights as an astrologer were valued by King Charles II.”23

Ashmole was also interested in Rosicrucianism, an occult religion which gained popularity in Europe during the 1610s. It was named after its founder, Christian Rosenkreuz, “who had learned great secrets during his travels to the Orient. Rosicrucian texts expounded a new mélange of Hermeticism and Christianity, and proclaimed the imminent dawning of a new spiritual age.”24 Perhaps Ashmole and others believed they were joining Rosicrucianism instead. After all, “the ritual of Hiram Abiff’s death and resurrection is thought to derive from Rosicrucian necromancy.”25 Suffice it to say that Ashmole was not alone in his hunger for wisdom or a new age of spiritual and moral enlightenment.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, Freemasonry gained power and prestige among the English elite. In need of the finest stonemasons to rebuild the city, the Crown employed Sir Christopher Wren, a brilliant architect, and his master mason, Thomas Strong, to lead the city’s rebuilding. Both Freemasons, Wren, Strong, and other Masons “became enormously wealthy on the public money that flowed into rebuilding England’s capital after the Great Fire.”26 Eventually, the building projects ended, leaving the rich Freemasons eager for more power and clout. In 1717, over fifty years after the terrible fire, the Grand Lodge in London was born. But now it seemed as if Freemasons were not merely interested in spiritual enlightenment or personal virtue. England would never be the same after the Civil Wars and the Glorious Revolution. The emerging political demarcations of Royalist “Tories” versus Parliamentarian “Whigs” provided a new opportunity for power and influence. For,

The birth of what would become the Grand Lodge took place just as the money to rebuild the City of London ran out, and just as the new Whig regime was establishing itself. The men who created the Grand Lodge were ambitious, formidable networkers, and all Whigs.27

Freemasons increasingly gained prestige through political avenues. They not only came to dominate the Whig party but also distinguished intellectual bodies such as England’s Royal Society, where top scientists and alchemists, including Isaac Newton, dazzled King George I with their experiments. Although it is unclear whether Newton himself joined the Masons, colleagues of his, like Dr. John Theophilus Desaguliers, and “all of the Secretaries of the Royal Society from 1714 to 1717 were Freemasons.”28 In the Royal Society, a marriage of Whig philosophy, Newtonian physics, and Freemasonry materialized, eventually becoming the philosophy du jour. If one were to dominate English society, Freemasonry provided the ticket. Thus, Whig statesman Sir Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain, joined the Freemasons.29

Chapter II: One Nation Under the ‘Great Architect’

This was the cultural, political, and intellectual milieu in which the Founding Fathers were born. Although the first English Mason to arrive in the American colonies was John Skene, who immigrated with his family to New Jersey in 1682 and eventually became the deputy colonial governor of West Jersey, Masonry predominantly spread through the British military. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, “England had outsourced much of the responsibility for creating overseas colonies to private companies, wealthy aristocrats, and religious sects safer to observe from afar.”30 However, England’s successful conquests of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, along with its increasing wealth in trade and goods from its expanding colonies, quickly transformed the small island nation into the most powerful empire on earth. Though the Seven Years’ War against France cemented England’s control over the North American colonies, the emerging imperial class of English aristocrats “sought to… subjugate the American colonies to their will, institutions, bureaucracy, and religion.”31

Thus, the presence of British military officers significantly increased in the decades leading up to the American Revolution. However, “wherever the British army went, Freemasonry accompanied it in the form of regimental field lodges… [where] often the colonel commanding would preside as the lodge’s original master.”32 This included the Commander-in-Chief of North America, Baron Jeffrey Amherst, who was initiated into Freemasonry as early as 1732. During his tenure as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army (1758-1763), Amherst successfully conquered New France in Canada with the help of the very colonists who would later rebel. These “Americans who served British contingents and received military training and instructions in strategy and tactics were also introduced to the rites and rituals of a branch of Freemasonry”33 that would eventually be known as the “Scottish Rite.” One of those young American officers was George Washington, the father of America.

But Washington was not unique. His compatriot, Benjamin Franklin, was also a Freemason, which he promoted in print after taking ownership of the Pennsylvania Gazette. He was also the Grand Master of the Pennsylvania Grand Lodge and became the Provincial Grand Master of the First (St. John’s) Lodge of Boston. The military was no different. Washington “was virtually surrounded by Masons”34 during his command of the American forces. As historian H. Paul Jeffers notes, “half of his generals belonged to the Craft, including France’s Marie-Paul de Lafayette and the Prussian army officer Baron Frederick von Steuben.”35

Similarly to the spread of Masonry in England, the occult society spread rapidly among officers, the very men who would ultimately form the founding political class of America. Though Thomas Jefferson was not a Freemason according to records, “sixteen of the fifty-six signers (28 percent) of the Declaration of Independence were either Masons or probable ones.”36 This was also the case in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention, where “Freemasonry was not only the single remaining pre-Revolution fraternal entity but also the sole organization operating nationally.”37 Divided across ethnic, denominational, professional, cultural, and class lines, the first generation of American leaders found in Freemasonry not only a unifying philosophical system but also a religious one. In this new system, according to Masonic scholar James Davis Carter, “philosophy had, for the first time in history, an opportunity to play a constructive role in the erection of a political and social order.”38

This would become a point of pride for later Masons, who saw their values expressly canonized in the Constitution. The supreme law of the land reiterates the sacred tenets of Freemasonry,

Including, religious tolerance, freedom of speech, a speedy trial according to law before equals when accused of law violation, no imposition of excessive punishment, reservation of all powers not delegated to the Constitution. A comparison of the principles of government universally adopted by Masons, with those contained in the Constitution, reveals they are essentially the same in both documents.39

Although we must consider Masons like Carter’s bias, it is notable that it was not the tenets of Anglicanism, Puritanism, Quakerism, or Catholicism that unified the Founding Fathers and inspired their chartering documents. It was Freemasonry.

In 1789, this same spirit would lead Washington’s inauguration as the first president of the United States. Chancellor Robert. R. Livingston, Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of New York, would administer Washington’s oath of office while General Jacob Morton, the Grand Secretary of that same lodge, would marshal the ceremony. Livingston used a specific King James Bible during the oath-taking, which included the inscription on the second page, “This important ceremony was performed by the Most Worshipful Grand Master of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York.”40 The Grand Lodge of New York received the Bible in 1770, and it would continue to be utilized at the inaugurations of Warren Harding, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, and George H. W. Bush. It would also become a mainstay of other ceremonies, including:

Washington’s funeral procession in New York, December 31, 1799; dedication of the Masonic Temple in Boston, June 24, 1867, and in Philadelphia in 1869; the dedication of the Washington Monument, February 21, 1885 (and its rededication in 1998); and the laying of the cornerstone of the Masonic Home at Utica, May 21, 1891. It was also used at the opening of the present Masonic Hall in New York on September 18, 1909, when St. John’s Lodge held the first meeting, and conferred the first Third Degree in the newly completed temple. It was displayed at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, at the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and at the Famous Fathers and Sons exhibition at the George H. W. Bush Memorial Library in Texas in 2001.41

Masons were not only a significant part of Washington’s inauguration but also his cabinet and the country’s governing leadership. 13 of the 26 initial U.S. Senators were Masons, and “the governors of the thirteen states at the time of Washington’s inauguration were Masons.”42 In addition, this list included Chief Justice John Jay and Associate Justices William Cushing, Robert H. Harrison, and John Blair. There was no denying that at the helm of the new country, Masons led the charge.

After the question of leadership was settled, the question of a national capital became paramount. Though many hoped to see New York (Alexander Hamilton) or Philadelphia (Benjamin Franklin) become the young nation’s epicenter of power, Washington chose the swampy no-man’s-land of northern Virginia (my hometown). After picking the site for the capital in 1790, Washington “was given all but unchecked authority to design and build what was initially referred to as the ‘Federal City.’”43 Three years later, “the city witnessed what the press [Columbian Mirror and Alexandrian Gazette] called ‘one of the grandest MASONIC processions,’”44 when now President Washington and his fellow Masons performed a cornerstone ceremony for Capitol Hill.

With Washington at the very end, a long procession of Masons, city commissioners, artillerymen, stonemasons, engineers, and musicians approached the scaffolding. The Masons had brought their ceremonial kit, which included “a Masonic Bible on a velvet cushion; an engraved silver plate; a silver trowel with an ivory handle; a walnut set square and level; a marble gavel; and finally golden cups containing the sacred wine, oil and grain.”45 After lowering the first stone, Washington applied the “square, symbolising virtue to make certain each angle was perfectly cut. The level, a symbol of perfect equality, to check that its placement was true. He then sprinkled the wheat, wine and oil to augur plenty, friendship, and peace.”46 In the year of Masonry 5793, Master Mason Washington had blessed what Jefferson deemed “the first temple dedicated to the sovereignty of the people.”47 With his brothers at his side, Washington ushered in a capital blessed by Masonry.

Such a religious ritual was appropriate for the New Republic, which, in many ways, emulated the ancient Republic of Rome. An inclusive civic religion had helped Rome conquer the Mediterranean. It had also helped bind the Romans into a unified mythology, which highlighted their cultural exceptionalism. Rome was great because Rome honored the civic gods, or so many Roman statesmen argued. In keeping with the spirit of post-Reformation occult religion, American Freemasons were inaugurating not just their new country but also the new age.

In contrast to the monarchical era of religious dogmatism and divine kingship, American Freemasons hoped to create a new era of tolerance, equality, freedom, and rationality. Rather than adhere to the canons of an authoritarian church or the complex and mysterious theologies of Trinitarian Christianity, Freemasons would initiate America into a religious culture that prioritized fraternal love and egalitarian unity. Under the grip of the Church, Western Europe had descended into the ‘Dark Ages.’ Now, under the Great Architect, it would introduce enlightenment.

In Part II, we shall explore how this spirit inspired America’s quest to manifest such a destiny by molding itself into the image of its creator.

"10 Quotes from Billy Graham on America," Billy Graham Library, Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 28 June 2016, https://billygrahamlibrary.org/blog-10-quotes-from-billy-graham-on-america/.

John Adams, Letter to Thomas Jefferson, 28 June 1813, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0208

Ibid.

About 20% of the American population identifies as Catholic, according to the Pew Research Center. Justin Nortey et al., “10 Facts About U.S. Catholics.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 4 Mar. 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/03/04/10-facts-about-us-catholics/.

Although the English Civil Wars (1642-51) preceded the American Revolutionary War by over a century, historians have often underestimated their impact on the makeup of early American culture. English colonists were split as bitterly as their brethren back in England. As Woodard points out, “Tidewater [the regional culture he associates with English colonists who initially settled in Virginia] and Yankee New England stood at the opposite poles of the mid-seventeenth-century English-speaking world, with diametrically opposed values, politics, and social priorities. And when civil war came to England in the 1640s, they backed opposing sides, inaugurating centuries of struggle between them over the future of America.” Colin Woodard. American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. (Penguin Books, Second Edition, 2022), 47.

Edwin Gaustad and Leigh Schmidt. The Religious History of America: The Heart of the American Story from Colonial Times to Today. (HarperCollins, Revised Edition, 2002), 136.

Ibid. 132.

Ibid.

To remain as objective as possible, I have consulted only Freemason sources for membership lists. "Famous Freemasons," Freemasons Community, freemasonscommunity.life/famous-freemasons/. Accessed 4 July 2025.

Despite corporate media’s depiction of such claims as “conspiracy theories,” historical evidence confirms that John D. Rockefeller, one of America’s richest and most powerful corporate oligarchs, funded and designed the American educational system for the Industrial Age. I encourage those interested in the topic to read more by John Taylor Gatto, a former inner-city public school teacher who helped expose the corporate, industrial nature of modern American education. For a primer on the subject, see https://www.saveourschools-march.com/why-did-john-d-rockefeller-create-the-school-system/.

Peter Feuerherd, "The Strange History of Masons in America," JSTOR Daily, 3 Aug. 2017, daily.jstor.org/the-strange-history-of-masons-in-america/. Accessed 20 June 2025.

Ibid.

John Dickie. The Craft: How Freemasons Made the Modern World (Public Affairs, 2020), 58.

Manly P. Hall. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. (Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, Reader’s Edition, 2003), 566.

John Dickie. The Craft: How Freemasons Made the Modern World (Public Affairs, 2020), 59.

Ibid., 22.

Ibid.

Manly P. Hall. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. (Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, Reader’s Edition, 2003), 568.

Ibid. 577.

Charles William Heckethorn. The Secret Societies of All Ages and Countries. R. Bentley and Son, London, 1875, p. 251, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/cu31924092567050/page/n273/mode/2up.

John Dickie. The Craft: How Freemasons Made the Modern World (Public Affairs, 2020),

Ibid. 40.

Ibid. 41.

Ibid.

Ibid. 42.

Ibid. 49.

Ibid. 52.

Ibid. 56.

"Chronology of Freemasonry: From 1390 - 1989," The Masonic Trowel, 9 May 2014, www.themasonictrowel.com/new_files_to_file/chronology_of_freemasonry_1390_1989.htm. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Colin Woodard. American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. (Penguin Books, 2012), 108.

Ibid.

H. Paul Jeffers. The Freemasons in America: Inside the Secret Society. (Citadel Press, 2007), 3.

Ibid. 4.

Ibid. 24.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. 26.

Ibid.

Ibid. 27.

Ibid. 28.

Ibid. 29.

Ibid.

John Dickie. The Craft: How Freemasons Made the Modern World (Public Affairs, 2020), 152.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. 153.

Ibid.

Americans are a Christian nation. The United States is a Judeo-Freemasonic construct.

Thank you! This is fascinating. I have a question. Do you think the post-reformation interest in the occult is a development from the fifteenth century humanist interest in Hermetic magic, like that under Pico della Mirandola, revived under the banner of reformation freedoms, or do you think they’re different movements altogether? I’m curious since there seems to be some revival of interest regarding hermeticism in traditionalist Catholic circles, which makes me uncomfortable, but I don’t know where to put that in the broader intellectual framework.